Curve, Leicester

Wednesday 29th March, 2023

‘With new life there’s new hope,

right?’

Malorie Blackman was a seminal figure in my adolescence and a

huge influence on my love of literature. I first read her Noughts and

Crosses series aged 13. To my maturing mind the books were revelatory; they

dealt with adult themes such as race, politics, sex and class, with striking confidence,

a gripping plot and without ever talking down to the reader. These were

grown-up novels and I ate them up with relish. In the 20 years since publication

Blackman’s story has gone from strength to strength, becoming a set text for

schools, spawning a hit BBC tv series, and now inspiring it’s second stage adaptation.

Sabrina Mahfouz’s version highlights the prescience and urgency of Blackman’s story,

conveying both the universality of the themes while emphasising their pertinence

in contemporary society.

Sephy and Callum have known each other all their lives, their

bond is seemingly unshakeable, yet the society they live in places them worlds

apart in terms of wealth, liberty, education and class. Sephy Hadley is a

Cross, the daughter of a top politician, living in an expensive house with its

own private beach, and all the material riches she could ever want. Callum McGregor

is a Nought, the son of the Hadleys’ maid, a lower-class citizen within a racially

segregated state built on oppression and capital punishment. A new government

policy permitting the integration of Noughts into Cross schools, along with the

increasing violence and unrest brought about by the extremist paramilitary group,

the Liberation Militia, forces Sephy and Callum to confront their differences

and question their place in social history. Political and personal clashes

ultimately end in tragedy in Blackman’s modern parable, which still holds the

power to shock.

Mahfouz stays true to the source material in her adaptation,

while adding her own linguistic flourishes that lift the piece into the realm

of drama. I particularly enjoyed Mahfouz’s sections of verse which portray the

inner thoughts of our protagonists. Internal rhymes and a striking use of

mirroring/repetition are earthily poetic while demonstrating both the confluence

of the characters and the incongruous, duplicitous systems which dictate their

lives.

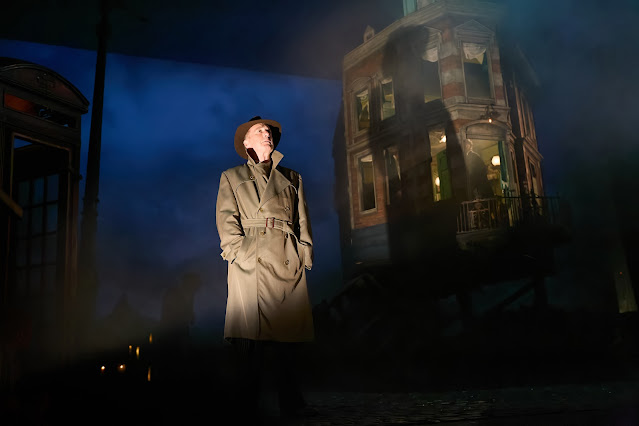

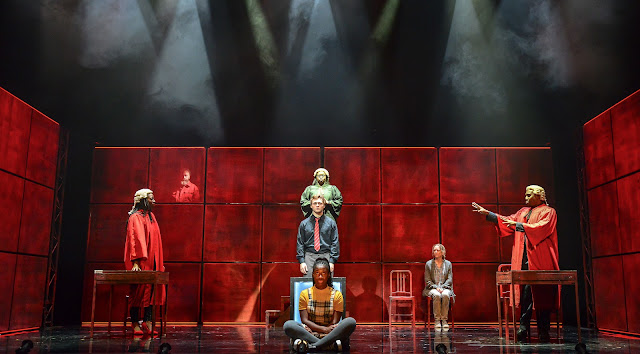

Simon Kenny’s deceptively simple design makes great use of

blocky, urban set pieces which occasionally melt into gauzy windows or burst

into pops of violence – whether rhetorical or physical – via Ian William

Galloway’s vast video projections that flood the stage. We are in a familiar

world of rolling news channels, shopping malls and mobile phones (although only

Crosses are permitted to own them), which hammers home the similarities with

the increased racial tensions in our own society over recent years.

If Esther Richardson’s production is a little rough around

the edges at times this does not detract from the narrative punch. In fact, the

lack of gloss and intimacy of the piece draws the audience into this world,

relying not on high tech theatrical wizardry, but old-fashioned story-telling

charm. Yes, Blackman and Mahfouz’s social commentary is painted in broad

strokes, but this plays well with the mainly teenaged audience, who were rapt and

enthusiastic throughout. Long may Noughts and Crosses inspire and fire

up generations to come.

|

| The cast of Noughts and Crosses Credit: Robert Day |